Exhibition

Review by Meg Reuland:

JAMES DRAKE'S CITY

OF TELLS at RHONA HOFFMAN GALLERY, CHICAGO,

JUNE 24 - JULY 29, 2004 (TEL: 312-455-1990)

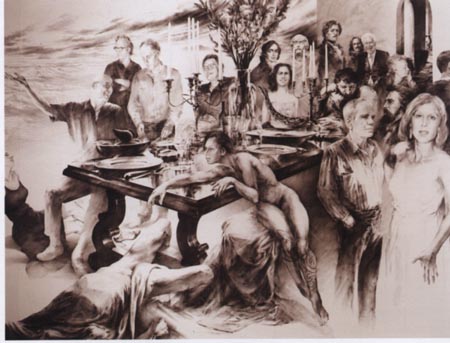

City of Tells,

(detail of 12 x 32 ft.

graphite on paper on canvas, 2002 - 04) James Drake

City of Tells, the

latest work of Santa Fe-based artist James Drake, has the visual grandeur

and spectacle of a Hollywood summer blockbuster. But, unlike those technology-dependent

ninety minutes of stunts and crunches, City of Tells (in gambler's

jargon, a "tell" is a revealing gesture or expression) shows an

achingly poignant and decidedly masterful human touch. The themes in City

of Tells may not bear profound scrutiny, but the show still haunts.

Drake is the kind of artist a viewer would love to watch at work, wielding his charcoal fiercely and fluidly across his vast pictorial spaces. Drake mobilizes every tone between inky black and negative white space to convince the viewer of the weight, texture, even color of his forms. Drake's sure hand renders the viscous drool of a hog and the dense smoke emerging from a cigarette, butt as convincingly as the solid limbs of figures and an effusion of drapery. Modeling is supple, yey edges are laser-sharp, a contrast that is both potent and eerie.

Drake crafts the scenes of monumental debacles, imbued with the drama and gravitas of nineteenth-century French Romantic painting. In City of Tells, With Signs Following, a python rips his way through a lavish feast, toppling the glassware, a candelabra, the wine, and sending cauliflower flying. Hogs pillage a similarly opulent banquet in City of Tells, Joy, Folly, Torment. The video component of City of Tells depicts this same action on a screen divided into thirds. In the two outer panels, a snake and hogs ravage the banquet. In the middle panel, the banquet is threatened, but never touched, by strange, loping figures in the grassy background.

In its excessive propriety-utensils for every course, multiple glasses for every guest, a whole turkey roasted to perfection and attended to by a vegetable medley-the banquet showcases the trappings of human culture. The demonic serpent and hogs invade this human world, wild and unchecked, and proceed to cause its downfall. The scenes' destruction is so thorough and freakish as to seem apocalyptic. They hint at a sinister affinity between the ravenous animals and human guests who would never come.

People are conspicuously absent from these scenes of destruction, but the series includes a number of portraits. One bust of a soldier in uniform is pieced together from patches of paper held together with masking tape. He appears again in the background of City of Tells, Dancing in the Louvre which shows an ecstatic modern couple who seem to have danced their way into a Fragonard painting. The title-piece of the series, City of Tells, is a group portrait spanning a whopping thirty-two feet, too big for the modest-sized Rhona Hoffman Gallery, but reproduced in the catalog. Based on Rafael's High Renaissance masterwork School of Athens, the tableau is populated by Drake's friends, family, favorite authors, philosophers, artists, cameos from myth and art history, and even Drake as a child.

Dancing in the Lourvre

(graphite on paper

on canvas, 2002 - 04) James Drake

These portraits explore what Drake calls his "motivation" for the series: how "tells" operate in human interactions. In gambling, "tells" inadvertently betray one's intentions or strategies; the opponent learns to read and to exploit such "tells." In the military portrait, Echo Rattlers Strike Hard Strike Fast Kill, the soldier's gaze is baleful and unmoored. In Dancing at the Louvre, he stares at the couple gravely, aloof. Glances dance across the mammoth City of Tells; each is subtle, loaded, and curious. These single and group portraits comprise Drake's contemplation of isolation, community, and history.

Echo Rattler Strike

Hard Strike Fast Kill

(graphite on paper on canvas, 2002 - 04) James Drake

The problem with the series as a whole is that the themes don't develop, engage, or enlighten each other; instead the series seems to pursue a number of separate projects. On the one hand you have animals crashing a bourgeois feast; on the other, intriguing casts of characters in improbable encounters. The connections, if they are there, seem too personal to register with the viewer.

In the end, City of Tells seems to be the term bundling Drake's work of a two or three period, not a coherent conceptual system. When each piece presents such a dramatic statement, the gaps in symbolic discourse feel like a loss. At the same time, however, each piece stands stolidly on its own merit, boasting such rare qualities of draftsmanship and compositional impact that the exhibit should not be missed.

--End--

Meg Reuland holds a B. A. in Art History from Yale University and studies modern and contemporary art.