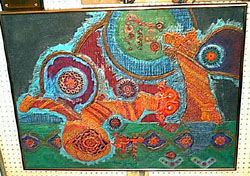

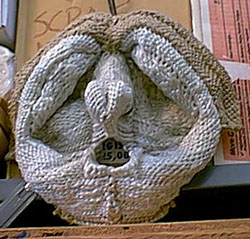

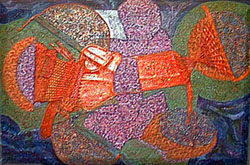

Rubin Steinberg is an artist who is best known for his assemblage bas-reliefs. The bas-reliefs are characterized by a heavily textured appearance that is actually varying types and gauges of woven rope and chord. From piece to piece the resulting impressions are very different. The weaving is often topographical with undulating peaks, valleys, and plains. Sometimes it is reminiscent of the knitting of muscle fiber or neurons. Other works have the industrial look of masses of electrical wires and circuit boards. Several pieces seem to be influenced by ethnic art. The assemblages are usually built up on a wood panel, where the painted fiber work evokes thoughts of a painting seen under a magnifying lens on a very inconsistent and loosely woven canvas. It's as if the irregular warp and weft of a canvas was being enlarged and then enlisted to serve in place of brush strokes. In addition to the woven elements of the bas-reliefs he tends to utilize leather, gears, brass repousse, cork, found woven materials (especially his mother's crochet work), and any other bits and pieces that strike his imagination.

Like yours truly, he is an artist that is driven by a fascination for unusual favorite materials. Similar artists are always most creative when they are playing and experimenting with pet materials. The sheer self-indulgent pleasure of the exploration of a chosen media gives them a distinctive voice, and unfortunately, sometimes a dismissible reputation. But, if a viewer can look beyond the use of peculiar materials, they will discover, at the very least, in Rubin Steinberg's work an abstract celebration of sensual delight. Besides having a mastery of textural design and composition, he is also an accomplished colorist and orchestrator of the phenomenal play of light from artwork to eye.

The following interview took place in the artist's home and studio. The purpose of my visit was to talk to him about his career and his participation in two shows at The Chicago Athenaeum. I was there to offer assistance about which of his newest pieces he should exhibit. My visit and the interview began with a tour of his extensive art collection of his fellow Chicago artists. Many of the artists he points out are or were members of the Chicago Society of Artists, the oldest continuous artist collective in the United States. (Rubin Steinberg is one of the exhibiting artists for the Chicago Society of Artists Exhibit at The Chicago Athenaeum March 16 through May 6, 2002.) He is articulate and very easy to interview. Mr. Steinberg was an elementary and high school art teacher for 38 years and is very informative and forthcoming about imparting information about his career and artwork. There are only a few times in the course of the tour through his home and studio where I needed interject with a question.

RS: "This gentleman died..oh seven years ago. That was (Fred)Rappaport he...you may see one of these pieces in the show, that the Chicago Society of Artists will be having."

JRM: "He's a member? Or he was a member?"

RS: "Yeah he was a member."

RS:..."and there might be

other pieces of other people. It turns out that I have about 20

pieces of people from the Chicago Society of Artists. So whatever

we can do. Then as we go on there are other things, I ran across

the mate to this downtown at the Thompson Center...not this one

but one that was printed at the same time. So stuff gets around

you know."

JRM: "Who is that? Misch Kohn?"

RS: "Yes, Misch Kohn." (Misch Kohn b. 1916 was a painter, printmaker and a professor at I.I.T.)

RS: "This over here is an Anderson piece that might be in the show also. We'll have to see what Barry Skurkis (President of the Chicago Society of Artists) comes up with. This is a piece of my work and that is an earlier piece. The bedroom stuff is here. Everything we collect we hang and find a space for it...and I'm out of space. Except for the little places up there."

RS: "Wherever we go we pick up stuff. That's a piece of mine."

JRM: "This one here?"

RS: "Yeah that little collage

work. I do a lot of collage."

"That's (Joshua)Kagenove. That may be in our show also."

"That's Rowena Fry. She's gone a long time now. This may

be in the show too."

"This is Sam Greenberg. I have a lot of his work."

JRM: "Is that a woodcut? It's so precise."

RS: "Yeah. Oh he was a good artist."

(Entering sitting room)

RS: "Let's see this is early Steinberg."

JRM: "So you've been a fiber artist. That is your first love."

RS: "Oh yes, Oh yes. I started out painting in oils then it sort of evolved into this. By accident. This is not an on-purpose thing just because everybody else was doing macrame. What I turned it into was sculptural weaving. It was like box weaving, you know. My backs are other people's fronts. So if you look at macrame you're looking at the other side of what's on these. And these are mounted on wood."

JRM: "You've stapled them onto wood?"

RS: "Nailed. Then glued. Then I remove the nails. They're really twice as long to do than a macrame artist. Because I'm building sculptural forms."

JRM: "Sure. That's really interesting. In some of my pieces I attach stringed beads by gluing the strings down. It's got a similar look. I haven't gone into the third dimension and begun bending the strings up. My work doesn't have this great topographical look to it."

RS: "I did. I will show you

other works downstairs that these works turned into."

"This one is leather. At this point I'm not doing this. My

hands have started to give me a little arthritis. So every once

in a while I work it into something else. This is all leather

and suede which nobody did."

JRM: "Yeah, this really different."

RS: "Totally-absolutely-nobody worked with leather and suede."

JRM: "What year are we talking about here when you were doing this?"

RS: "1970. Could be in the 70's."

JRM: "Most of these are in the 70's?"

RS: "Yeah 70's going into the 80's. People didn't understand this stuff, I think I was way ahead."

RS: "This one is a Judy Roth she'll be in that show also."

(In the stairwell to basement)

JRM: "That's fantastic! It looks like two frames put together that are about 12x12"."

RS: "Yeah that's a nice piece. A little strange for some people.They're two blocks of wood. What I did was I used hinges at the ends to put them together then I worked on top."

JRM: "They're all assembled. You've got the fiber work going through here. You've got the interior of clocks and little pieces of hardware."

RS: "Right it's an assemblage. One of my student's fathers when I was teaching, you know I taught in the school system for 38 years, and one of the students fathers was in the gear business so she used to bring me the broken gears, so sometimes she'd come with a bag of broken gears and I'd use them in these assemblages. As the gears ran out, I began to do impressions of the gears."

JRM: "I see in the piece next to it you've got the impressions of the gears. It's just beautiful."

RS: "Likewise in the piece

over here. That'll give you a pretty good idea. And I collect

masks, since I make masks. Like the one in back of you. This piece

is all paper, paper and leather. I submitted it to a show at the

Art Institute, but they didn't like it. But it's all paper and

leather."

"This little piece is all sewn to the canvas, every bit of

it is sewn to a canvas. Some of it is screwed to the stretcher."

JRM: "There are all kinds of hinges and chains even. And then you go over it with different kinds of paint?"

RS: "Actually I stripped it three times and repainted it."

JRM: "It's got an incredibly rich patina over it. It looks like metal plate or old encrusted metals that have conglomerated and embedded and rusted together."

RS: "There's bed sheets, see that's old old torn sheets. Also needle and thread work. And then watch parts and clock parts."

RS: "Over here, with that sculptural weaving I can make the masks on any surface. That's what I did here. And like my friend up here."

JRM: "So there is a mask incorporated in here, it's just flattened out?"

RS: "Right. It comes from the wood. And some of my mother's crochet work is in there."

JRM: "That's great that you've been able to bring other fibers into these too."

RS: "And Burlap."

JRM: "Another interesting thing about your fiber weaving, they're of many different materials and of differing sizes all within the same artwork. You get a rich multi-textured appearance."

RS: "I like the contrast of materials and the raised areas and recessed areas. This particular piece I like very much. I think I had it out one time. I had it out to a show somewhere. The name of it is "Snobird"."

(Going down to the basement)

RS: "My wife and I went on a trip to Australia, Tahiti, Fiji, New Guinea and we somewhere along the way in a museum I saw a weaving that finished off the piece the way that I now finish off (some of) my pieces. I just stood in front of it for about 5 minutes, it occurred to me that I should be doing this on my work."

JRM: "That was a eureka moment for you, huh?"

RS: "Yes, This piece over here was in the 1970, no, 1968 Art Institute and Vicinity Show, I think I won some kind of an award for it, I'm not sure. That other big one that was upstairs on the wall in the bedroom is another one. That was in 1973. After I did this one I decided to do this one and here they are."

RS: "This down here is the 'rope factory'."

JRM: "Do you make all of your own fiber, or..?"

RS: "Oh, no, no. I bought fiber. I found a guy who had a fiber factory. I swapped him a piece of artwork for which he gave me about 400 lbs. of rope. I mean rope is heavy anyway.. dead weight. I used the 400 lbs. of rope and the gears and I had myself a good time. I still haven't run out of rope. I got three boxes of it back there."

RS: "These are the kind of sculptures that I made for a while. Then it occurred to me that I'm running out of room. I had no where to stand them and nothing to do with them. I wasn't getting into shows with them and so I just...you know. So I started working flat again."

RS: "This painting over here was part of my Masters Degree at the Art Institute. They're a little dusty."

JRM: "Did you have a title for this one?"

RS: "I don't think I ever titled it. That one you have there a drawing board and two halves (of a circle)."

JRM: "You really hit on a great surface for that with that red."

RS: "Now these things...there are two of them hanging here. This one hasn't seen the light of day since I made it. It's behind this other one. One can only guess what is living in there. It's a nice piece I enjoy it. And these are the little masks."

JRM: "What would you say besides the macrame from the 70's are your influences?"

RS: "My influences are ethnic art and Indian art, but you have to take it a couple of ways because, my first influence is Van Gogh. As I was painting and working when I was younger it occurred to me that if Van Gogh had kept painting, if he'd have lived, and he'd kept doing his sculptural painting eventually it would have turned into this. Because he was really getting sculptural in the way he used his paint. The reason I'm working in rope was I couldn't paint the way that Van Gogh did, I could take rope and manipulate it the way Rubin Steinberg does. And so this is one of the first ones. Also, this is using my mother's crochet. This other piece. The later ones like I had at your other show are back in here."

"You know I'm like a sponge

every artist I saw influenced me, made me go a certain direction

for a while. Then I'd come back and combine these directions.

These are all masks in here. They're all masks these little guys.

You'll see in my other studio. This was my studio for 20 years.

This is where I got my arthritis on this floor."

(Moves to some painting storage

stacks)

"But back here is the early work. I did a lot of line work.

Here's another one like that other. And I did a lot of oils, collages..collage

is my thing. It's called "Tiny's Chimes"."

JRM: "What kind of year are we talking about here?"

RS: "I guess it's late 60's

early 70's. I won't go through all this stuff for you. This is

assemblage. This is 1970. Motorcycle parts. The whole place is

filled with this kind of stuff. The whole shebang. What I didn't

do in that stuff, I did out of in things. Like this is a little

case. It was a window frame. It was like a porthole. I stretched

some canvas and then worked some leather over it."

JRM: "Oh that's leather! Did you just buy old scraps of leather

and then .."

RS: "There's a place that makes coats in Chicago I don't know if it's still there, Rubin Grayas coat company. It was on Western Avenue and what I used to do was go there and get bags of this stuff. I took it to school to work with my students and I used it myself."

JRM: "What school did you teach at?"

RS: "I taught at Wicker Park and I taught at Curie High School. Wicker Park is now Pritzker."

"This is a character."

(Steinberg menaces me with a rope sculpture that has an upper set of dentures)

JRM: "OH! IT's GOT TEETH!"

JRM: "This is some of your drawing work?"

RS: "Yeah I do a lot of line work. I'm going to show you what I thought, I wasn't sure whether you wanted the stuff that's over there."

(We carefully navigate to the other side of the room.)

JRM: "How many pieces would you say you finish in a month?"

RS: "It depends on if I'm busy. I'm also a docent at Block Museum. So if I keep churning em out I can churn out 2 or 3 a week. It depends on the size of the piece too. When I got through teaching in 1995, all of a sudden it was like an explosion. I was making art and making art making art. I'll show you over there in a minute."

RS: "This one over here is one of my favorites. These are beads."

JRM: "It's beautiful, what were these little paper beads?"

RS: "No. No those are wood.

These are, oh, old pressed paper tubes. It's a good piece.

I'll tell you, you need strength and youth to sit there and manipulate

this little stuff."

JRM: "Are you weaving directly on to the boards as you go?"

RS: "Directly on the board."

JRM: "So you didn't weave a piece and then applique it."

RS: "Right. Here's a pair of my pants on this one. This piece is called "Tubin' Beads""

JRM: "What year is that?"

RS: "I have no idea. Oh in the 70's."

JRM: "Where did you learn fiber work?"

RS: "I learned it myself."

JRM: "You taught yourself. Were there manuals or anything from which you could pick up basic techniques?"

RS: "No, I taught it to myself."

JRM: "No. You just picked it up and started to manipulate the material."

RS: "I was doing a collage and weaving. And I was teaching a class in collage to a bunch of old ladies. One little old lady says to me, "Oh you're doing a square knot.""

JRM: "And you said, Oh really? There's a name for this?"

RS: "I didn't know what a square knot was. What's a square knot? She was a very nice little lady who showed me what a square knot was. But what I was doing was just overhand looping and pulling as tight as I could. Every once in a while I would have to stop and let my hands heal."

JRM: "It's kind of interesting because as an art piece that hangs on the wall, it is still evocative of canvas. You know it's like canvas that's gone mad in a way."

RS: "Right. People always sort of associated it with snakes."

JRM: "Well, I don't see the snakes."

RS: "I figured it was what they were drinking."

JRM: "What is this a 3-D mask?"

RS: "No it's just a sculpture. I was learning my craft and having a good time."

JRM: "You don't need to use any kind of starch to keep these constructions rigid?"

RS: "No you don't need a thing. The rope has body. The more you manipulate the rope, the tighter it gets, the stiffer the rope gets. So if you are a weaver this is a lesson for you."

JRM: "I'm not really a weaver at all. I'm just sort of playing with my own favorite stuff like you are. I'm still trying to figure out what works and what doesn't."

RS: "Anything can be used. I have one out there made out of Saran Wrap. I'll show you a little mask I made out of Saran Wrap."

RS: "These are all early pieces that I started on em and I just kept going."

JRM: "Is this in progress?" (Indicating a woven sculpture suspended from the ceiling)

RS: "No I stopped working

on this years ago. The thing actually hung down to the floor.

What I did was just pull it up and tied it in. It created a good

shape."

RS: "This one is like a piece of beef."

JRM: "It really does have that shape, doesn't it?"

RS: "Yeah, I showed this stuff to the director of the museum at Block and he liked it but they're not going to give me a show. There's no room for this kind of stuff. It's almost frightening. It isn't New York, you know."

JRM: "It's very Chicago."

RS: "Yes, it's very Chicago."

RS: "This one is a neat little piece. This is the one that the teeth came out of." (Another woven sculpture)

JRM: "Look at this! Did you make this?"

RS: "No that's a kid's glove.Oh I use assemblage."

JRM: "You are even picking up old found woven stuff?"

RS: "Right. I use a lot of found fiber. This was my first real collage right there. You know, I work on little things like these I get to a point and then I say, Oh the Hell with it!. It was going to be a mask and then it was going to be a figurine. Then I just thought that's good enough."

JRM: "I see repousse metal work incorporated into some of your pieces. Even in a mask up here."

RS: "That's a..It's more than just a mask, it's two sided."

JRM: "It looks a little bit like a Tiki guy or an African thing."

RS: "I was teaching my students how to do work with repousse."

JRM: "In grade school you were teaching repousse?"

RS: "In both grade school and high school, I showed them how to manipulate the copper. First they were working in aluminum. Of course anything that I did, I later put into my assemblages."

"The director of the museum really loved that one he wanted to buy it. But he went to Wellesley University so that was the end of that."

"Here are some crayon and Cray-pas drawings."

JRM: "Did any of your drawings become the preliminary sketch for one of your woven wall assemblages?"

RS: "It's rare. When I do

something each one is an individual piece. It is what it is. The

design is always there. The method is different."

JRM: "You are always trying something new?"

RS: "Yeah, always trying something new."

JRM: "You don't have too many klunkers. When I experiment, I get a lot of rejects."

(Steinberg indicates a huge bin of full of paper pieces)

RS: "I do all kinds of drawings."

JRM: "Some of these are very sculptural."

RS: "Yeah. See I really like sculpture. I would have liked to take some of these and turned them into sculptures but I don't have space. I don't have space, I don't have the equipment."

"What else here. Stuff, stuff stuff. And it's fun. I enjoy it."

JRM: "Are you still teaching at all part time?"

RS: "No. I really should."

RS: "Here are the ones I was thinking of back here. If you send framed stuff to Europe it's going to cost you an awful lot to ship. But if you send shrink wrapped pieces, I think you'd be better off. But you want a show and you want to show framed pieces."

JRM: "The difficulty is they have no money in Lithuania, they have no cash to devote to this project. So I'd have no way of getting it framed."

RS: "Then I'll find you something that is framed. I was thinking of something like this one. Which is leather collage."

JRM: "That is nice. That's actually a very good candidate."

RS: "I try not to do too many klunkers."

JRM: "What I meant by good is that it is a good example of the kind of style that I enjoy looking at by you."

RS: "Every once in a while I take one of the pieces and I will roll it up with ink and I will print it. So I did three or four prints of this kind of thing also. Upstairs I did a lot of mono prints, that I'll show you later."

JRM: "What is the technique on this one?"

RS: "It's cut leather and I'll show you the original upstairs, how I did this kind of thing."

JRM: "The plate is leather?"

RS: "The plate is leather. This is a cork print here. What I'm doing is multiple printings of material and cork and just reproducing. All of the materials that I make assemblages out of I use to make prints."

(Pulls out an assemblage panel)

RS: "These are pistachio nuts on this assemblage here. Of course the weaving. This next one is called " Chuck's Keys". "Chuck's Keys. " Chuck was a very good friend. He was a teacher at one time. These are from the Chicago Board of Education they are stamps and this was a little pouch we found in his house. We cleaned it out. It was about six months of work cleaning out his art garbage. This is from when he was in the Marines. Those are his keys and of course he was Jewish. I put in a little star. Chuck knew about Indian lore. This is sort of a take off on Indian copper. From northwest coast Indian. There are things in that pouch, I took some of his stuff and put it in there."

(Pulls out another piece)

RS: "This over here is a whole new shebang. I've got overlapping curtain material in order to make this background on this piece. It gives you a very interesting effect on the artwork."

RS: "I handled this rope thing in several ways. See there is another one over there under glass. What I did was I went to see this very nice man named Mr. Colgut Mr. Colgut had a drapery store, once upon a time, on Broadway. Mr. Colgut used to give me the rolls of take off cord. When he would put up somebody's drapes, Mr. Colgut would take off the old rope, he'd roll it onto a big roll, and he'd put it aside. He was a very smart man. He would use it to wrap bundles and stuff. When I went there Mr. Colgut was very kind and he gave me several rolls. What I liked about it, when I went to the Field Museum I saw the remnants. The old Egyptian remnants. They were the bits and pieces they pulled out of the tomb. This is downstairs in the basement. When I looked at Mr. Colgut's rope that he gave me to play with, all of a sudden I could see the remnants. Because the sunshine fades these things, people handled them, they get oil on them, they change color over the years. So that's what I did with these things I turned them into remnants. So they're actually very historical, there is no name and phone number on them but they are part of our society. This is what we used at one time to pull the drapes."

(We go upstairs to his current studio)

JRM: "So when you are first putting together your woven assemblages this is what they look like?"

RS: "That one actually could be finished. Unless I wanted to give it another coat. I was thinking of darkening this. This one could stand as it is."

JRM: "The other ones have a top coat of paint over the texture to unify everything."

RS: "This one is at the point, it's been sitting here for about five months. It's at the point where I want to darken some of this. I'm going to use a wash, a dark wash in here. So that these things stand out."

JRM: "Start to pop?"

RS: "Right. So these are all things that are in process. Now I've started something new. Working at the Block Museum. This is something that nobody has done. That I know of. What I'm doing here is that I'm tearing this board in order to create these textures."

JRM: "This is mat board?"

RS: "Yes. When you tear them you get the lines of the layers of the mat board, see?"

JRM: "Mm hmm."

RS: "When you do that all of a sudden I'm back to my lines again that I get with my rope. So if you look at it close that's done with crayon and Cray-pas."

JRM: "It looks like stone or layers of stucco."

RS: "Mm hmm, well o.k. I'm just getting used to them."

JRM: "You're keeping some of the mat board top color like in this one here."

RS: "Yeah, so I've been playing with 'em. I'm having a good time with it. I'll show you just for the hell of it, I'll show you the mono prints."

(End of Interview)

Rubin Steinberg is sometimes described as a self-taught artist, however, self-taught or outsider artists tend to be culturally isolated. He does use an intriguing mix of traditional and non-traditional materials which range from humble arte povera or art brut fare like rusty gears, rope, cork, macramé-like weaving, and other cast offs, to beautifully crafted brass repousse work and acrylic paint, all combined with a virtuousic sense of design. He can be called 'outsider' in one respect for sure; Steinberg's admirable creative integrity and loyalty to his pet technique-woven rope and chord-is nothing short of martyrdom when one considers that the connotations of 'macramé' in the fine arts is mere degrees more positive than for sock monkey sculpture. Although he has taught himself the individual crafts that are assembled together in his work, Steinberg's sense of composition and finesse belie an immersion in a culturally sophisticated environment and a distinguished education.

This passage about Paul Klee is resonant in a discussion of Rubin Steinberg's work:

"The monument of Klee's

obsession with this metaphysics was a singular book, The Thinking

Eye, written during his teaching years at the Bauhaus - one of

the most detailed manuals on the "science" of design

ever written, conceived in terms of an all embracing theory of

visual "equivalents" for spiritual states which, in

its knotty elaboration, rivaled Kandinsky's. Klee tended to see

the world as a model, a kind of

orrery run up by the cosmic clockmaker - a Swiss God - to demonstrate

spiritual truth. (1)

And

"Like Kandinsky, Klee valued the "primitive," and especially the art of children. He envied their polymorphous freedom to create signs, and respected their innocence and directness.(1)

Steinberg values and is inspired by the primitive as much as Paul Klee. Unlike Klee, Steinberg is not searching for the quintessential primitive symbol. He utilizes primitive material and composition then refines and enriches it with design like wetting a stone to enhance its luster.

Steinberg's aesthetic is partially inspired by the freedom given to artists by the founders of dada. Especially, Kurt Schwitters, who ran with Duchamp's assertion that art can be made from any material an artist sees fit. Schwitters became infamous for incorporating all kinds of salvaged (sometimes prankishly stolen) detritus of modern culture into his collages and assemblages. Some of Kurt Schwitter's paintings from 1919-1920 like Merzbild 29A (Picture with Flywheel,) Star Picture, and Circling would look quite at home among the stacks of four decades of assemblages in the Steinberg home and studio. There is a similarity of merz materials, color and abstract composition, but Steinberg has added the writhing and dancing textures that are physically delightful and far too retinal to be considered a direct descendent of the dada school. For, each of Steinberg's assemblages is a visual record of a wrestling match between the wild horses of disparate and unruly materials and the artist's playful efforts to tame, reign and weave them into a disciplined and polished work that expresses the artist's triumphant mastery and joy of process. Above this exuberant baseline, canters the emotional collage that gives each piece it's distinctive rhythm and mood.

Sources

(1)Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

Marjorie Perloff, Dada Without Duchamp / Duchamp Without Dada: Avant-Garde Tradition and the Individual Talent

Susanne Gudowius, researcher and editor, Berlin VGTV, Seevetal, www.kurt-schwitters.org (with Google translation from German)

Louise Dunn Yochim, How to Understand and Appreciate Abstract and Non-Objective Works of Art, LDY Special Publications, 1999 (Exclusively spotlights the artwork of Rubin Steinberg to illustrate the publication's main points.)

Louise Dunn Yochim, Role and Imapct: The Chicago Society of Artists, Chicago Society of Artists, 1979.

In the Studio with Rubin Steinberg is copyrighted by Julie Reichert-Marton 2002